Cultural Symbiosis and Aesthetic Reconstruction: When Chinese Porcelain Met the Gemstone Inlay Craft of Ottoman Empire in the 16th Century

-

摘要:

奥斯曼帝国凭借地缘优势成为东西方贸易的重要枢纽,并在16世纪实力达到鼎盛。在此期间,大量的中国瓷器通过丝绸之路贸易网络输入,成为苏丹皇室的珍贵收藏,这激发了本土工匠的艺术创作灵感——运用独特的宝石镶嵌工艺对中国瓷器进行改装重饰。这类宝石镶嵌瓷器约占现今土耳其托普卡帕宫博物馆藏中国瓷器总量的3%,是文明交流过程中文化共生与审美重塑的典型案例,为“一带一路”历史研究提供了重要的实证样本。本研究以托普卡帕宫博物馆藏的273件宝石镶嵌瓷器为对象,采用观察法,辅以历史文献考据与图像学分析,系统分析了其获取途径、工艺美学(材质特征、装饰纹样、镶嵌手法等)及改装重饰缘由,旨在探讨奥斯曼工匠对中国瓷器的工艺改造技术、文化转译逻辑及其承载的社会功能。研究发现,奥斯曼工匠运用“网状包覆法”与“星状点缀法”宝石镶嵌技术对中国瓷器进行二次艺术加工,将其转化为融合伊斯兰艺术元素的宫廷瑰宝,实现了器物功能的在地化转变(如酒器转作净手器)与文化符号的重构(如郁金香纹样金属饰板的象征意义);同时还对宝石镶嵌和镶扣(mounting)两种工艺的特征进行了辨析。这些改造实证不仅提升了器物的实用价值与艺术价值,更为中西方交流中“文化共生与审美重塑”现象研究提供了新的研究视角。

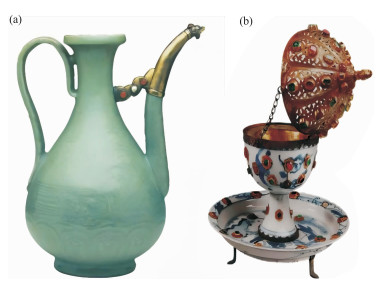

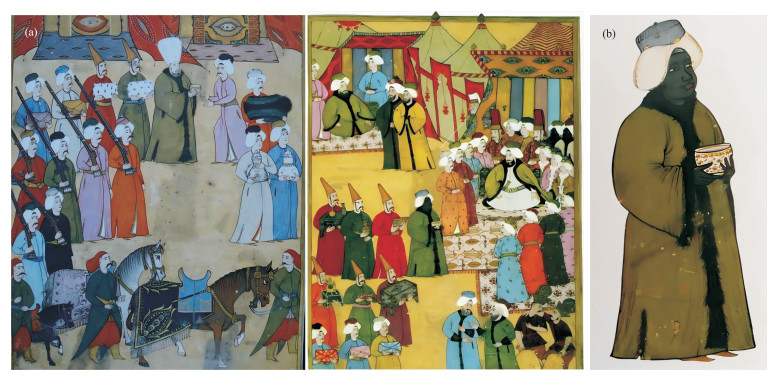

Abstract:The Ottoman Empire, capitalizing on its geopolitical advantages, emerged as a pivotal center for East-West trade and reached its zenith in the 16th century. A substantial volume of Chinese porcelain was entered into the empire via the Silk Road trade network and collected by the Sultan's royal household. This influx inspired local craftsmen to redecorate these porcelains using a unique gem inlay technique. Today, these gem-inlaid porcelains, accounting for about 3% of the Chinese porcelain collection in Topkapi Palace Museum in Turkey, are typical examples of cultural symbiosis and aesthetic reconstruction within civilizational exchanges, which provieds a valuable empirical sample for "Belt and Road" historical research. This study focuses on 273 gem-inlaid porcelains from the Topkapi Palace Museum, employing observational method, along with historical literature review and iconographic studies.It analyzes the acquisition routes, craft aesthetics (including material features, decorative patterns, and inlay methods), and the reasons for redecoration. The aim is to explore the technical modifications, cultural translation logic, and social functions of Chinese porcelain by Ottoman craftsmen. The research reveals that Ottoman craftsmen utillized the "mesh covering method" and "star-like dotting method" for gem inlay, transforming the Chinese porcelain into imperial treasures integrating Islamic art elements. This process facilitated the functional localization (e.g. converting wine vessels into ablution utensils) and the reconstruction of cultural symbols (e.g. the symbolic meaning of tulip-patterned metal plates).Additionally, the study also differentiates between gem inlay and mounting techniques. The transformation of Chinese porcelain by Ottoman craftsmen not only enhanced the practicality and artistry of the objects but also provided a new perspective for studying the phenomenon of "cultural symbiosis and aesthetic reconstruction" in Sino-Western exchanges.

-

Keywords:

- export porcelain /

- gem-inlaid porcelain /

- Ottoman Empire /

- Topkapi Palace Museum /

- trade history

-

-

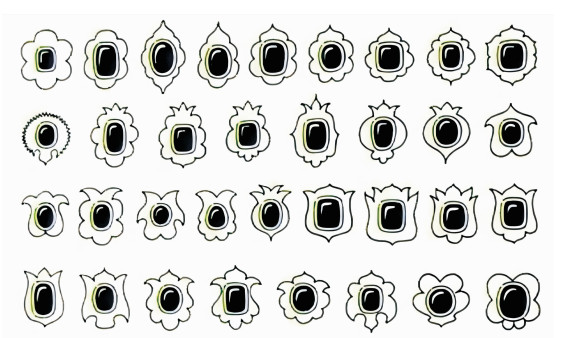

图 2 工艺中的宝石切割样式和金属饰板样式[15]

Figure 2. The gemstone cutting styles and metal trim styles in the craftmanship

-

[1] 中国与土耳其: 小亚细亚两端的世界图景[J]. 文明, 2021(Z2): 6, 146-161. Turkey-China: World atboth ends of Asia minor[J]. Civilization, 2021(Z2): 6, 146-161. (in Chinese)

[2] 李小成. 从汉代史书的"西域传"看古丝绸之路诸国之物产[J]. 唐都学刊, 2019, 35(4): 71-77. Li X C. On the products of the countries along the ancient silk road based on the historical books The Western Regions Annals in the Han Dynasty[J]. Tangdu Journal, 2019, 35(4): 71-77. (in Chinese)

[3] 马文宽. 中国瓷器与土耳其陶器的相互影响[J]. 故宫博物院院刊, 2004(5): 78-96, 157. Ma W K. The influence of Chinese porcelain in Turkey[J]. Palace Museum Journal, 2004(5): 78-96, 157. (in Chinese)

[4] 王晓明. 世界贸易史[M]. 北京: 中国人民大学出版社, 2009: 651. Wang X M. World trade history[M]. Beijing: China Renmin University Press, 2009: 651. (in Chinese)

[5] Taskin B. Topkapi Palace the Imperial Harem — House of the Sultan[M]. Istanbul: BKG Yayinlari, 2012: 354-355.

[6] Efendi S M. Seranic biography[M]. Istanbul: Unknown publisher, 1989: 90.

[7] 爱赛·郁秋克. 伊斯坦布尔的中国宝藏[M]. 欧凯, 译. 伊斯坦布尔: 土耳其外交部, 2010: 126. Yutyuk A. A Chinese treasure in Istanbul[M]. Ou K, translated. Istanbul: Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Turkey, 2010: 126. (in Chinese)

[8] 曾涛. 论元明时期青花瓷在西亚北非的传播及其影响[D]. 太原: 山西师范大学, 2022. Zeng T. Spread of the blue and white porcelain in West Asia and North Africa during the Yuan and Ming eras[D]. Taiyuan: Shanxi Normal University, 2022. (in Chinese)

[9] 张向荣. 奥斯曼帝国宫廷生活中的中国瓷器[J]. 北大区域国别研究, 2024(2): 128-139. Zhang X R. Chinese porcelain in the Ottoman courtlife[J]. PKU Journal of Area Studies, 2024(2): 128-139. (in Chinese)

[10] 张廷玉. 明史[M]. 北京: 中华书局, 1974: 8 626-8 627. Zhang T Y. The history of Ming Dynasty[M]. Beijing: Zhonghua Book Company, 1974: 8 626-8 627. (in Chinese)

[11] 海斯, 穆恩, 韦兰. 世界史[M]. 冰心, 译. 北京: 生活·读书·新知三联书店, 1975. Hayes C J, Moon P T, Wayland J W. World history[M]. Bin X, translated. Beijing: SDX Joint Publishing Company, 1975. (in Chinese)

[12] 裴度, 葛建军. 土耳其托普卡比王宫博物馆收藏的中国瓷器[J]. 收藏家, 1997(5): 60-61. Pei D, Ge J J. The collection of Chinese porcelain in the Topkapi Palace Museum of Turkey[J]. Collector, 1997(5): 60-61. (in Chinese)

[13] Dankoff R, Kim S. An Ottoman traveller, selections from The Book of Travels of Evliya Celebi[M]. London: Eland Publishing, 2011: 437.

[14] Durucu N. Suleiman the Magnificent: An Ottoman sultan and jeweler[J]. Adornment, The Magazine of Jewelry & Related Arts, 2017, 11(1): 3-16.

[15] Krahl R, Erbahar N, Ayers J, et al. Chinese ceramics in the Topkapi Saray Museum Istanbul: A complete catalogue[M]. New York: Sotheby Parke Bernet Pubns, 1986.

[16] Galland A. Istanbul'a ait günlük Hatιralar (1672-1673)[M]. Ankara: Türk Tarih KurumuYayιnlarι, 2018: 20.

下载:

下载: