| Citation: | GAO Xinxin, WEN Shangjia, LU Ren. Cultural Commonality and Diversity: Aesthetic Journey of Turquoise and Lapis Lazuli along the Ancient River Valleys[J]. Journal of Gems & Gemmology, 2022, 24(5): 190-204. DOI: 10.15964/j.cnki.027jgg.2022.05.018 |

千万年来,人类以有限的生命续写历史,宝玉石则以恒久的物质状态与人们相伴而行。宝玉石因坚硬辅助人类劳动,因美好装饰人类身躯,也因珍贵引起人类相争。伴随地壳板块运动等系列复杂演变过程,大自然适逢机遇才幸得孕育宝玉石。仅产自少数矿区的宝玉石能够显身于世界各地古老遗址,离不开人类活动。宝石难以腐朽,往往保存完好,追溯宝玉石的物质史,亦是回望人类的历史。随着现代测试技术的发展,宝石学研究在鉴别、产地溯源、颜色定量测试等方面为珠宝贸易提供严谨判断依据的同时,也为探寻人类历史真相不断提供新的科学证据。

宝玉石为何、如何与人类精神信仰密切关联,很早就引起学界关注。费孝通[1]曾提出将玉器同我国传统文化与精神文明相结合,挖掘中华文化的鲜明特质与优秀传统,使之与世界各国文化相互交流、融合发展。玉器考古研究[2]围绕玉器的材质、器型、纹饰、工艺及功能等方面形成了玉文化系列讨论,肯定中国玉文化的独特性。此外,叶舒宪[3]曾提出每一个文化都有其独特的玉石或宝石观念,须认识与把握世界性的玉石崇拜现象,摒弃“华夏独有”的片面立论。尽管世界各民族少有“以玉比德”的文化现象[4],却普遍存在崇尚美石的观念。在促进东西方文明交流与融合发展的道路上,不仅需要挖掘玉文化的独特价值,还应该把握东西方文化之间的共性。各文化环境所呈现的人类行为与社会规范有着明显相似性[5]。

回归人类对于客观物质的自然认识过程,宝玉石的色彩往往最先被察觉,然而以往玉文化相关论述却较少聚焦于这一直观的视觉语言。绿松石与青金石是受到世界上多个民族共同喜爱的宝玉石。笔者从视觉色彩出发,以绿松石和青金石为例,聚焦中国、埃及、两河流域三处文明发源地,追溯人类与宝玉石之间的互动关系,探寻人类文明共通的美石崇拜观念,旨在为推进东西方宝玉石文化交流与融合发展系列研究提供参考。

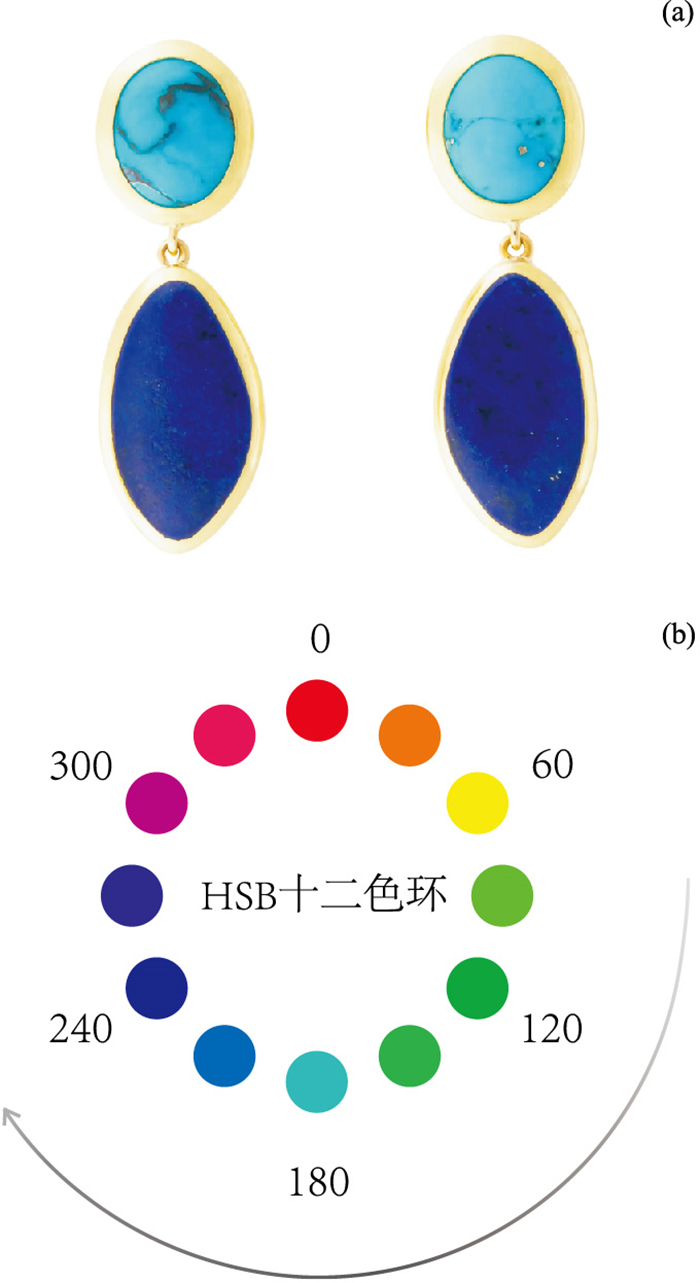

现行国家标准《绿松石分级》基于HSB颜色分级体系为绿松石设置颜色分级规则及参考色卡[6]。绿松石的色相(H,Hue)范围为12°~220°,其中绿蓝色至蓝色区间(H:160°~220°)样品占比78.8%[7]。虽以“绿”命名,绿松石的颜色实以蓝色为主。有学者同样借助HSB颜色体系将我国先秦时期色彩“青”的色相值归为87°~239°(绿色至深蓝色)[8]。“青”与绿松石、青金石的色相范围基本相符(图 1)。人眼并不能直接将色彩识别为数据,但在现代色彩科学出现以前,人们依然能通过色彩进行表达与交流。盘古化生万物的神话传说展现了古人将自然万物比作自己最熟悉的身体来认识大自然的过程。“他的血液变成了江河,经脉变成了道路,肌肉变成了田土,头发和鬆须变成了天上的星星”[9]。人类认识色彩的过程与之相似。

天空之湛蓝,海洋之蔚蓝,皆令人心旷神怡,人们对蓝色的喜爱几乎是世界性的。事实上,人类经历了很长一段时间才真正分辨出蓝色。视觉感知色彩依赖于人眼的“捕捉器”(视觉神经),其中识别蓝色的“捕捉器”数量最少,意味着人类天生较难分辨蓝色[10]。身处低明度环境,人们易将蓝色、绿色与黑色混淆,如图 2。语言学研究曾提出基本色彩词诞生及发展的普遍顺序,蓝色晚于黑色、白色、红色、黄色[11]。早期语言少有单独描述蓝色的色彩词[12]。例如,中国传统色彩词“青”不仅用于描述蓝色,还指向绿色,甚至黑色[13]。类似的,古希腊语“glaukos”可描述蓝色、灰色、黄色或棕色,“kyaneos”可形容深蓝色、紫色、棕色或黑色[14]。

在没有色度数据标注色彩的过去,“以物代色”是人们常用的交流方式。青金石和绿松石可用于描述色彩[12]。青金石在我国古代有着“金精”“绀琉璃”等称谓,佛教经典描述佛陀和菩萨的发色为“绀瑠璃色”,佛发、佛眉、佛眼为“金精色”或“青琉璃”,可理解为像青金石那样的颜色[17]。苏美尔文献中月亮神有着“像青金石一样(lapis lazuli-like)”的胡须[18]。古阿卡德语(Akkadian)“uqna”意为青金石,也指如青金石般深蓝色的玻璃制品[18]。古埃及荷鲁斯神(Horus)有着如青金石般蓝色的双眼[19]。绿松石曾以“瑟瑟”之名出现于唐代贸易记载中[20]。唐朝诗人白居易常用“瑟瑟”描述青绿色彩,犹如“一片瑟瑟石,数竿青青竹”(《北窗竹石》)。与将青金石指代色彩的方式相似,古埃及与美索不达米亚等地也有“像绿松石一样(turquoise-like)”的语言表述[19]。“像青金石一样”与“像绿松石一样”成为人们认识自然、理解自然与传递色彩信息的方式,青金石蓝与绿松石蓝继而日渐融入人类社会与文化中。

绿松石与青金石参与人类生活的时间可追溯至新石器时代,于文明发源地——黄河流域、尼罗河流域、两河流域的文物遗存中可寻觅二者踪迹。

我国中原地区绿松石使用历史可追溯至距今约9 000年的贾湖文化。绿松石与早期巫神信仰密不可分,也与身份象征有关。考古学者在贾湖遗址第一、二期墓葬中发现了大量的随葬绿松石(图 3a, 图 3b),第一期(距今9 000—8 500年)墓葬中存在绿松石瞑目葬俗的最早例证,第二期(距今8 500-8 000年)随葬绿松石串饰的墓葬相对集中在遗址中心区域,表明当时社会在墓葬等级和分区上已有一定程度分化[21]。此后,绿松石随葬品普遍存在于黄河中上游地区具有仰韶文化传统的文化脉络中,例如仰韶文化、马家窑文化、陶寺文化中期、二里头文化等遗址[22]。

至新石器时代晚期、二里头时期,绿松石镶嵌物在黄河流域发挥着重要作用。前人研究[23]认为,二里头遗址具有都城性质,是迄今为止可确认的、我国古代文明中年代最早的都城遗址。精美绿松石装饰品用于象征使用者的身份地位,大型礼仪性质的绿松石镶嵌器物则用于祭祀或巫神仪式。其中,二里头遗址二期(约公元前1740—前1600年)出土的绿松石龙形器引人瞩目(图 3c, 图 3d),是罕见的中国早期龙形象文物[24-25]。相传龙协助大禹治水有功被夏人视为圣物,夏人的器物多以龙形为饰,绿松石龙形器与传说中夏人的象征性图腾相符,它很可能展现了夏文化中的“龙”形象[26]。该龙形器由超过2 000片绿松石组成,形象灵动,颜色近于均一,形状较为规整,摆放有序[27]。据我国绿松石形貌特征以及现行绿松石分级体系[6-7],夏人能够筛选出颜色均一、表面洁净的绿松石,应当具有一套较为完备的绿松石分拣流程。从贾湖到二里头,从散见的小颗绿松石,到大型的绿松石镶嵌器件,大量广泛出土的绿松石文物显示了绿松石曾鲜活地存在于早期华夏文明社会生活中,体现着先民对绿松石的喜爱与追求。在二里头遗址之外,盘龙城遗址杨家湾商代墓葬也出土了类似的使用绿松石片组合成龙形的文化遗存,被称为“金片绿松石兽形器[28]”。我国先民将系列精神思索寄托于绿松石,将其视作珍贵的神物。

在古埃及,绿松石与青金石被认为是神灵力量的化身[32]。古埃及人使用绿松石历史可追溯至距今大约6 500—6 000年的巴达利亚文化(the Badarian)[33-34]。至古埃及中王国时期(约公元前2030—前1640),不仅皇室贵族墓葬中有丰富的绿松石珠宝饰品,沿尼罗河从北到南的非皇室墓葬中也发现了绿松石护身符、珠子和镶嵌物[35]。早在前王朝时期(约公元前3500年),古埃及人就大量使用了青金石,用作串珠、镶嵌,或用作护身符[36]。最具代表性的是发掘于古埃及第十八王朝图坦卡蒙(Tutankhamun)陵墓中的精美胸饰(图 4a,约公元前1341-前1323年),中央为青金石雕刻而成的圣甲虫,左右镶嵌绿松石与青金石片,组合成为护身符。古埃及第十二王朝的西塔霍尤内特公主(Princess Sithathoryunet)墓葬出土的胸饰(图 4b,约公元前1887-前1878年)同样可视作护身符,象征着墓主的皇室身份,其上镶嵌的宝石以绿松石与青金石为主[37]。深蓝色的青金石有时带有金黄色黄铁矿颗粒,犹如笼罩着大地的无垠星空。青金石多用于建造神,说古埃及阿蒙神(Amun)有着蓝色肌肤,被称作“青金石之神(Lord of lapis lazuli)”[38]。绿松石则与哈索尔女神(Hathor)有着密切联系,哈索尔又被称为“绿松石女神(Lady of the turquoise)”[39]。

古中国之西方,古埃及之东方,亚欧大陆的中心——西亚是亚欧东西方往来联结必经之地。这片广袤的土地上有着丰富的宝玉石资源,其中就包括绿松石与青金石。在涵括两河流域及其周边地区的西亚一带,青金石与绿松石的使用历史可追溯至距今约9 000—8 000年。位于现伊朗西北部地区的特佩扎格(Teppe Zagheh)遗址(约公元前6250—前4750年)曾发掘出少量绿松石、青金石串珠[42];约公元前3500年,位于现伊拉克北部地区的特佩高拉(Tepe Gawra)遗址曾发现大量青金石与绿松石珠饰[43-44];位于现伊朗东北部地区的桑格查赫马克(Tappeh Sang-e Chakhmaq)遗址(约公元前7000—前5300年)也曾发现少量绿松石串珠[45]。此外,美索不达米亚早期第三王朝时期(Early Dynastic Ⅲ Period,约公元前2600—前2334年)出土了非常丰富、精美的青金石文物[43],包括坠饰、雕刻有宴会场景的圆柱形印章以及装饰器件等。最具代表性的是乌尔皇陵墓葬(the Royal Cemetery at Ur)中由青金石、黄金、银等材料制作的雕像(图 5,公元前2450年)。苏美尔文献多次提及青金石的珍贵,它用作护身符,参与神庙建造,是苏美尔人赠予神的礼物[46]。

此后,波斯第一帝国(Achaemenid Empire,约公元前550—前330年)以及伊斯兰世界(The Islamic World,大约公元7世纪至19世纪)等多个时期当地都延续了崇尚蓝色的传统。波斯诗歌常用绿松石和青金石描述自然界的色彩,形容蓝色的天空与花朵[47]。在当地人心中,绿松石是神圣的,是一切美好事件的象征。源自绿松石的蓝色在帖木儿时期(Timurid Dynasty)成为中亚地区伊斯兰教的代表颜色,形成了伊斯兰文化最具特色的印记[48]。

绿松石与青金石的用途普遍与天神有着密切关联,两者的色彩与仰头可见的天空遥相呼应。绿松石的蓝色明快,介于蓝绿之间,似晴空之蓝,似水之碧色。青金石的蓝色显得深邃,时有颗粒状金黄色闪光,似星光闪烁的寂静夜空。绿松石与青金石的蓝色与河水、蓝天等有利于日常生活的自然环境色彩相似,神秘却能够给予人们安全感。相较于神秘天境,绿松石与青金石是人们能够触碰的有形物质。绿松石与青金石成为承载人类信仰的圣物,不仅受到人类主观意识具象化、可视化需求的驱动,还必须依赖于人们能够获取相应的宝玉石资源。

绿松石与青金石的大量使用及相应制作工艺的长期发展,必然基于稳定的绿松石与青金石资源,即可供应人们需求的采矿点。目前发掘的矿点遗址保留了古人采矿活动的痕迹,所涉及的部分矿区至今仍然持续向人们供应优质的宝玉石。人类对绿松石与青金石的追寻不仅促进了矿产资源开发,也促进了贸易流通网络的形成,绿松石与青金石随着消费需求流向文明发源地。总体上,黄河流域、尼罗河流域、两河流域周边都发现有绿松石矿床资源(图 6),各地开采年代不尽一致。而三地附近均尚未发现青金石古矿址,所用青金石的来源都以阿富汗巴达赫尚矿区为主。

我国目前发现的绿松石古矿遗址主要分布在中原黄河中下游一带以及新疆哈密黑山岭一带。位于中原地区陕西省洛南县洛河沿岸的河口矿业遗址发现了10处古代开采绿松石的洞穴遗址,其开采年代约为公元前2030—前500年,即始于新石器时代晚期至青铜时代早期,延续到春秋时期[51],是二里头文化绿松石的来源之一[52]。位于同一矿带的湖北郧县云盖寺也被认为是二里头绿松石来源之一,但未发现古矿遗址[53]。基于目前考古发掘相关证据,中原是我国最早使用绿松石的地区,尽管尚未有明确证据追踪到年代更早的绿松石古矿址,但不能排除中原地区是否有更早开采绿松石的可能。在西北地区,位于新疆哈密的黑山岭、天湖东2处绿松石古矿遗址至少距今约3300—2400年,可能是该区域早期绿松石原料的重要来源[54]。其中,黑山岭遗址矿区存在大量采矿遗迹,年代为距今约2650—2380年,被认为是目前新疆地区年代较早、规模最大的一处古代采矿遗址,也是目前我国规模最大的早期绿松石矿业遗址群[55]。在内蒙古阿拉善右旗浩贝如地区也发现了古代绿松石采矿遗址,年代大约为东周时期(公元前770年—前256年)[56]。

伊朗内沙布尔是世界上重要的绿松石产地之一[57],其中伊朗达姆甘(Damghan)、内沙布尔(Nishapur)、克尔曼(Kerman)等地区开采铜矿及绿松石矿床历史悠久[35, 58]。位于伊朗高原的史前绿松石开采遗址尚未被发现,有学者推测伊朗北部内沙布尔及南部克尔曼地区可能大约在公元前4000年或者更早的公元前7000年开始开采绿松石,但同样尚未有确凿的证据[34, 58-59]。埃及附近的西奈半岛(Sinai)西南部有着古老的绿松石采矿遗址,瓦迪(Wadi El-Maghara)与塞拉比特(Serabit el-Khadim)是古埃及人开采绿松石的2个主要遗址[35, 39, 60]。瓦迪遗址被认为是最古老的古埃及绿松石矿区,早在古埃及第一王朝(First Dynasty of Egypt,约公元前3100—前2900年)就被开采[60-61],遗址附近的岩壁上刻有古埃及第三王朝(the Third Dynasty)三位国王的名字——萨纳赫特(Sanakhte)、内杰里克赫特(Netjerykhet)、塞赫姆赫特(Sekhemkhe)[62]。此外,在古埃及中王国时期(the Middle Kingdom,约公元前2055—前1650年),古埃及采矿队在塞拉比特遗址开始了大规模的采矿活动[63],该遗址附近的石壁上记录了与绿松石相关的文字信息,可见第十二王朝(ⅩⅡDynasty)的有关记载,还发现有祭拜“绿松石女神”哈索尔的神庙[39, 64]。

开采历史悠久的阿富汗巴达赫尚(Badakhshan)矿区应是古代青金石最重要的来源[43, 65]。在公元前约4000—前3000年,来自阿富汗的青金石广泛分布于中亚至古埃及一带,主要集中在伊朗高原、两河流域及尼罗河流域[66]。阿富汗巴达赫尚附近的法罗尔丘地(Tepe Fullol)遗址(约公元前2600—前1700年)是青金石贸易网络的重要证据。这里不仅发掘了装载有金银器、青金石等物品即将驶向伊朗高原与两河流域的商船,还发掘出可用于制作青金石串珠的工具,说明该地曾是青金石贸易集散地与加工聚集地[67-68]。青金石到达古埃及需要再经两河流域商人之手,古埃及墓葬遗址与两河流域墓葬遗址中青金石数量存在同时期空缺可佐证两地之间的贸易关系[43]。青金石从阿富汗巴达赫尚向西经过伊朗高原、两河流域,流向古埃及,形成了一个成熟完善的青金石贸易网络[68](图 6)。色彩象征与视觉体验影响着宝玉石的消费需求与经济价值,宝玉石因此更可能参与长途贸易[68]。伴随着青金石贸易自巴达赫尚向西不断拓展,青金石之美持续向西传播。

而青金石向东之路并不如前者畅通,青藏高原系列高海拔山脉与高原是最直接的地理阻碍。一般认为,青金石可能因贸易从瓦罕走廊(Wakhan)流向我国西域,沿“绿洲丝绸之路”,到华北、中原等地区[69-70]。青金石也可能随游牧民族沿“草原之路”进行贸易,自乌兹别克斯坦,经天山北麓、蒙古高原,进入我国北方地区[71-72]。我国目前发现青金石文物的最早年代为东汉时期(公元25—220年)[73]。早期青金石饰品均发现于王室贵族墓葬,例如东汉洛阳烧沟横堂墓曾被误认为是玻璃制品的青金石耳珰[74-75],东魏、北周等时期墓葬(约公元534—581年)也发现有镶嵌青金石金饰[74, 76-77]。艰难险阻未能阻挡青金石进入我国,青金石所承载的文化观念与信仰也随之来到东方,与华夏民族精神文化相融。藏传佛教文化中药师佛(Bhaishajyaguru)被尊为藏族医术之源,其身为深蓝色青金石,有象征治愈之意[78]。至清朝时期,皇室信奉佛教,乾隆皇帝推崇藏传佛教,将佛教仪式纳入国家祭祀体系[79]。皇帝佩戴青金石朝珠参与祭天仪式以彰显统治理念,朝珠便是由佛珠演变而来[80]。古代南方丝绸之路被称为“中印文化走廊”,沿途可见佛教文化相关文物遗存[81]。青金石有可能沿此路自印度途经缅甸进入云南、四川、西藏等地。从阿富汗向西到美索不达米亚再去古埃及,向东到古印度以及古中国(图 6),承载着独特蓝色的青金石一次又一次地被选中,寄托着、传递着人们对天空神灵的敬仰与崇拜。

尽管自新石器时代起,绿松石与青金石资源就被人类开采、收集和应用,有限的资源仍然难以满足人们的需求。人们试图模仿绿松石与青金石,并寻找相应的替代品,如费昂斯(Faience)、玻璃、陶器、瓷器、珐琅器等人工制品[82-83]。从而,人们能够通过相似的物质载体表达自然崇拜。色彩是绿松石与青金石最直观的特征,模仿也由此开始。彩色人工制品的普及使得绿松石与青金石色彩更广泛地融入人类社会生活,延续着早期信仰,传递着宝玉石色彩美。

汉代王充在《论衡·率性篇》[84]中提到,“道人消烁五石,作五色之玉,比之真玉,光不殊别”,其中“五色之玉”指用玻璃仿制的宝玉石,玻璃也被称为“琉璃”[85]。我国玻璃制作技术诞生于战国至两汉时期(公元前475—公元220年)[86]。新疆地区出土的西汉时期(约公元前202年—公元8年)仿制绿松石的玻璃珠是古人制作玻璃仿制宝玉石的最直接证据[87]。湖北江陵望山一号楚墓(春秋战国时期,约公元前770—前221年)越王勾践剑剑格的正反面分别镶嵌了绿松石和蓝色玻璃,当时人们很可能将蓝色玻璃等同于绿松石[88-89]。同时期的楚墓出土了大量仿玉玻璃制品,包括璧、环、印、剑饰等礼仪性质器物,以湖南地区出土仿玉玻璃器最为丰富,颜色以浅绿色居多,平民阶级墓葬中也可见到玻璃璧[90-91]。湖南益阳战国深绿色谷纹琉璃小环,如图 7。

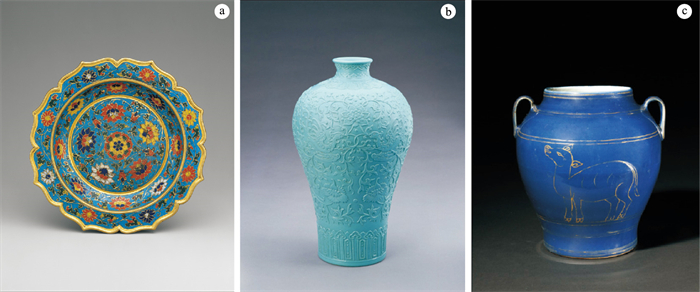

华夏民族喜爱青色不仅见于仿玉玻璃制品,还可见于珐琅器、陶瓷器上的蓝色釉面。景泰蓝(铜胎掐丝珐琅)的鲜明特色在于以“蓝地”为背景,以红、黄、深绿、深蓝色等色彩做纹饰(图 8a,约公元15世纪)。其中,“蓝地”也被称为“绿松石蓝”,深蓝(钴蓝)釉色如青金石蓝色[93]。陶瓷器各色釉彩发展丰富于明清时期(公元1368—1912年),松石绿釉诞生于清雍正年间(公元1722—1735年),色泽似绿松石[94]。乾隆时期(公元1736年—1796年)松石绿釉梅瓶,如图 8b。祭蓝釉(也称祭兰釉、霁青釉)犹如青金石般深蓝色,是明清两代常见的瓷器釉色[95]。明弘治时期(公元1488年—1505年)祭蓝釉金彩牛纹双系罐,如图 8c。在清朝祭天仪式规定“天坛正位登用青色瓷”[96],此处“青色瓷”即祭蓝釉色瓷器[95]。

费昂斯(Faience)也被称为釉砂,是部分玻璃态和晶态石英砂的混合体,一般被认为是玻璃制品的前身[36]。古埃及费昂斯的制作历史可追溯至大约公元前4000年[83]。自诞生起,费昂斯与玻璃都曾被视为宝玉石的替代品,或一种人造宝玉石,常与宝玉石一同出现在墓葬出土的串珠饰品中[100]。费昂斯多呈串珠状、管状或圣甲虫等形制,不透明,颜色有蓝色、绿色、红色、黄色等,其中护身符圣甲虫的色彩大多与绿松石、青金石相似[101]。例如古埃及第十八王朝哈特谢普苏特神庙出土的圣甲虫(图 9a,约公元前1479—前1458年)和古埃及第十九王朝胸饰品中的圣甲虫(图 9b,约公元前1275年)。公元前2000年的古埃及玻璃制品大多是随葬品,且部分出自皇家墓葬[102]。至中王国时期(约公元前2040—前1782年)费昂斯的使用非常普遍,见于各个社会阶级墓葬中[103]。

费昂斯还用于制作神像,古埃及护身符、神像等一切与神灵有关物品的色彩装饰中大多可见到蓝色[106]。人们赋予神灵以源自绿松石、青金石的蓝色[107]。例如,古埃及第十九至二十二王朝的绿松石蓝努特女神像(图 10a,公元前1296—前712年)。天空女神努特(Nut)象征着孕育与新生[108],以及古埃及第十八王朝的青金石蓝荷鲁斯之眼戒指(图 10b,公元前1550—前1295年)。荷鲁斯之眼(Eyeof Horus)象征着天神荷鲁斯为人类抵抗邪恶[109]。

美索不达米亚玻璃体系不同于古埃及,两地玻璃制造很可能是各自发展形成的[112]。“美索不达米亚的玻璃模仿了宝玉石,不仅有青金石和绿松石的蓝色,还有类似带状玛瑙的各种颜色”[34]。受古埃及和美索不达米亚地区物质与文化传播影响,蓝色玻璃在北欧地区同样备受珍视,例如当地人用蓝色玻璃与琥珀组成串珠作为护身符[113]。出土于丹麦胡姆卢姆(Humlum)地区的美索不达米亚蓝色玻璃(图 11, 约公元前1300-前1100年)。

在创造“宝玉石”之后,人们又将蓝色应用于建筑外观装饰。美索不达米亚宇宙观认为,神的居所(“天堂”)的地面由蓝色砖块铺造而成,即与晴空亮蓝色或与夜空深蓝色相似[115]。蓝色建筑暗示着其与神的关联,这一观念或许持续影响着后来的建筑装饰色彩。建于公元前6世纪的古巴比伦伊什塔尔门(The Ishtar Gate)城墙主要由釉面黏土砖块建造而成,釉面装饰的背景颜色以亮蓝色与深蓝色为主[116],如图 12a。古巴比伦铭文记录了尼布甲尼撒二世在位期间(Nebuchadnezzar Ⅱ,公元前604—前562年)使用青金石装饰城墙[117]。蓝色釉面不仅应用于黏土砖块上,还见于彩色釉瓷上。始建于1611年(波斯帝国阿巴斯一世在位时期),位于现伊斯伊斯法罕的沙阿清真寺(Isfahan Shah Mosque)建筑的釉面色彩同样以亮蓝色、深蓝色为主色,如图 12b。这两类蓝色又一次呈现绿松石蓝色与青金石蓝色的视觉体验。在宝玉石本体之外,源自绿松石与青金石的色彩广泛应用于人类社会生活,早期信仰与观念因而留存并延续于人类文明中。

费孝通先生晚年提出“各美其美,美人之美,美美与共,世界大同”的设想,描绘了“和而不同”、多元文化共存与互动的世界图景[1]。此处“美”原指“美好社会”,表现为神话、传说、宗教、祖训等多种形式,是群体共同认可与维持的行为准则和价值体系[120]。人类社会都具有对于“美好社会”的信念,各群体所认定“美好社会”的具体内涵体现着各群体的个性[120]。群体与群体之间的共识是促成多元文化交流的基础。

基于视觉感知的色彩认知过程具有普遍性[11]。人类认识自然和理解人与自然关系的过程依赖视觉感知,也呈现出共性。绿松石与青金石的色彩同天空、河水等人们日常所见、赖以生存的自然环境色彩相似。古中国、古埃及、美索不达米亚文明的“美好社会”信念中均存在绿松石、青金石与以天空为代表的自然神灵的密切关系,绿松石蓝色与青金石蓝色都曾作为自然神灵的视觉象征。各民族都饱含对于生活的美好期望与信念,期盼得到神灵庇护,在祭祀或崇拜仪式中应用绿松石、青金石以及它们的色彩以多种艺术形式表达自然崇拜。从开采资源、贸易交换到制作仿制品,绿松石蓝与青金石蓝自上而下地传递着群体的共识,更进一步维系着群体所处社会的行为准则与价值体系。同时,基于古中国、古埃及、美索不达米亚文明各民族对于绿松石蓝与青金石蓝的共识,各民族群体的交往互动带动着多元文化的交流互鉴,发展出各具特色、丰富多彩的艺术形式。色彩依托物质,物质建构生活。源自绿松石与青金石的独特色彩依托各式物质载体留存于人类文明中,这些物质文化遗产共同构成多元文化“美美与共”的和谐景致,传递着宝玉石色彩美。人们将绿松石与青金石带入人类社会并基于它们进行再创造的同时,源自绿松石与青金石的独特色彩依托于宝玉石、费昂斯、陶瓷、珐琅、建筑等物质载体持续塑造着人类社会生活。

稀少珍贵的宝玉石多被赋予各个历史时期最为重要的文化内涵。宝玉石以其恒定的色彩,承载着来自远古的精神信仰,持续守护着人类文明的重要文化信息。探讨东西方宝玉石文化交流与融合发展,不仅需要挖掘各文化的个性,还应当发掘文化的共性。在视觉感知普遍现象与色彩认知普遍规律的基础上,依托于宝玉石的稳定色彩能够为挖掘文化的共性提供更多的可能性。随着宝石学及相关学科快速发展,有关宝玉石产地来源、加工工艺等方面的科学研究还将为追溯人类历史提供更多线索。

| [1] |

费孝通. 费孝通论文化与文化自觉[M]. 北京: 群言出版社, 2005: 419-422, 529-545.

Fei X T. Fei Xiaotong on culture and cultural consciousness[M]. Beijing: Qunyan Press, 2005: 419-422, 529-545. (in Chinese)

|

| [2] |

刘国祥. 中国玉器考古研究方法与实例探析[J]. 江汉考古, 2019(5): 138-144. https://www.cnki.com.cn/Article/CJFDTOTAL-JHKG201905016.htm

Liu G X. Research methods and examples of Chinese archaeology in jade[J]. Jianghan Archaeology, 2019(5): 138-144. (in Chinese) https://www.cnki.com.cn/Article/CJFDTOTAL-JHKG201905016.htm

|

| [3] |

叶舒宪. "玉器时代"的国际视野与文明起源研究——唯中国人爱玉说献疑[J]. 民族艺术, 2011(2): 31-41. https://www.cnki.com.cn/Article/CJFDTOTAL-MZYS201102006.htm

Ye S X. The international perspective of "jade age" and the study on the origin of civilization: Only Chinese love jade is doubtful[J]. National Arts Bimonthly, 2011(2): 31-41. (in Chinese) https://www.cnki.com.cn/Article/CJFDTOTAL-MZYS201102006.htm

|

| [4] |

荀况. 荀子[M]. 方勇, 李波, 译注. 北京: 中华书局, 2011: 492.

Xun K. Xunzi[M]. Fang Y, Li B, translated. Beijing: Zhonghua Book Company, 2011: 492. (in Chinese)

|

| [5] |

Brown D E. Human universals, human nature & human culture[J]. Daedalus, 2004, 133(4): 47-54. doi: 10.1162/0011526042365645

|

| [6] |

全国珠宝玉石标准化技术委员会. 绿松石分级: GB/T 36169—2018[S]. 北京: 中国标准出版社, 2018: 1-14.

National Technical Committee on Jewelry and Jade of Standardization Administration of China. Turquoise-Grading: GB/T 36169—2018[S]. Beijing: Standards Press of China, 2018: 1-14. (in Chinese)

|

| [7] |

何翀, 曹扶芳, 狄敬如, 等. 国家标准《绿松石分级》解读[J]. 宝石和宝石学杂志(中英文), 2018, 20(6): 7-17. https://www.cnki.com.cn/Article/CJFDTOTAL-BSHB201806002.htm

He C, Cao F F, Di J R, et al. Interpretation of national standard turquoise grading[J]. Journal of Gems & Gemmology, 2018, 20(6): 7-17. (in Chinese) https://www.cnki.com.cn/Article/CJFDTOTAL-BSHB201806002.htm

|

| [8] |

肖世孟. 先秦色彩研究[M]. 北京: 人民出版社, 2013: 53-54.

Xiao S M. A study on color of Pre-Qin[M]. Beijing: People's Publishing House, 2013: 53-54. (in Chinese)

|

| [9] |

袁凤. 中国神话传说: 从盘古到秦始皇[M]. 北京: 世界图书出版公司北京公司, 2011: 53.

Yuan F. Chinese myths and legends: From Pangu to Qin Shihuang[M]. Beijing: World Publishing Corporation, 2011: 53. (in Chinese)

|

| [10] |

Stockman A. Cone fundamentals and CIE standards[J]. Current Opinion in Behavioral Sciences, 2019(30): 87-93.

|

| [11] |

Berlin B, Kay P. Basic color terms: Their universality and evolution[M]. California: University of California Press, 1991: 4.

|

| [12] |

Busatta S. The perception of color and the meaning of brilliance among archaic and ancient populations and its reflections on language[J]. Cultural Anthropology, 2014, 10(2): 309-347.

|

| [13] |

Wang T. Color terms in Shang oracle bone inscriptions 1[J]. Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies, 1996, 59(1): 63-101. doi: 10.1017/S0041977X00028561

|

| [14] |

Pastoureau M. Blue: The history of a color[M]. New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 2001: 23-26.

|

| [15] |

Turquoise and lapis earrings in 18 karat gold[EB/OL]. [2022-03-20]. https://www.1stdibs.com/jewelry/earrings/drop-earrings/turquoise-lapis-earrings-18-karat-gold/id-j_5897002/.

|

| [16] |

Pixabay. Mount Fitzroy, Patagonia, Mountain[EB/OL]. [2022-03-20]. https://pixabay.com/photos/mount-fitzroy-patagonia-mountain-2225382/.

|

| [17] |

郑燕燕. 从地中海到印度河: 蓝色佛发的渊源及传播[J]. 文艺研究, 2021(6): 138-150.

Zheng Y Y. From the Mediterranean to the Indus: The origin and spread of Buddha's blue hair[J]. Literature & Art Studies, 2021(6): 138-150. (in Chinese)

|

| [18] |

Thavapalan S. The meaning of color in ancient Mesopotamia[M]. Leiden: Brill, 2019: 310-312.

|

| [19] |

Schenkel W. Color terms in ancient Egyptian and Coptic[C]// MacLaury R E, Paramei G V, Dedrick D. Anthropology of Color: Interdisciplinary Multilevel Modeling, 2007: 211-228.

|

| [20] |

Bretschneider E. Mediaeval researches from Eastern Asiatic sources: Fragments towards the knowledge of the geography and history of central and Western Asia from the 13th to the 17th century (Vol. 1)[M]. London: Trübner & Co., 1888: 140, 175.

|

| [21] |

杨玉璋, 张居中, 蓝万里, 等. 河南舞阳县贾湖遗址2013年发掘简报[J]. 考古, 2017(12): 3-20, 125. https://www.cnki.com.cn/Article/CJFDTOTAL-KAGU201712001.htm

Yang Y Z, Zhang J Z, Lan W L, et al. The excavation of the Jiahu site in Wuyang county, Henan Province in 2013[J]. Archaeology, 2017(12): 3-20, 125. (in Chinese) https://www.cnki.com.cn/Article/CJFDTOTAL-KAGU201712001.htm

|

| [22] |

丁新. 中国文明的起源与诸夏认同的产生[D]. 南京: 南京大学, 2015: 35-37.

Ding X. The origins of Chinese civilization and the generation of "Zhu Xia" identity[D]. Nanjing: Nanjing University, 2015: 35-37. (in Chinese)

|

| [23] |

杜金鹏, 许宏. 二里头遗址与二里头文化研究: 中国·二里头遗址与二里头文化国际学术研讨会论文集[C]. 北京: 科学出版社, 2006.

Du J P, Xu H. Erlitou site and Erlitou Culture: Proceedings of the international symposium on Erlitou site and Erlitou Culture, China[C]. Beijing: Science Press, 2006. (in Chinese)

|

| [24] |

夏商周断代工程专家组. 夏商周断代工程1996—2000年阶段成果报告: 简本[M]. 北京: 世界图书出版公司, 2000: 76-77.

Expert Group of Xia, Shang and Zhou Dynasty Dating Project. Report on the achievements of Xia, Shang and Zhou dating project from 1996 to 2000: A brief version[M]. Beijing: World Publishing Corporation, 2000: 76-77. (in Chinese)

|

| [25] |

许宏, 赵海涛, 李志鹏, 等. 河南偃师市二里头遗址中心区的考古新发现[J]. 考古, 2005(7): 15-20. https://www.cnki.com.cn/Article/CJFDTOTAL-KAGU200507002.htm

Xu H, Zhao H T, Li Z P, et al. Recent archaeological discoveries in the central area of the Erlitou site in Yanshi city, Henan Province[J]. Archaeology, 2005(7): 15-20. (in Chinese) https://www.cnki.com.cn/Article/CJFDTOTAL-KAGU200507002.htm

|

| [26] |

郑杰祥. 二里头遗址新发现的一些重要遗迹的分析[C]//杜金鹏, 许宏. 二里头遗址与二里头文化研究: 中国·二里头遗址与二里头文化国际学术研讨会论文集. 北京: 科学出版社, 2006: 18-23.

Zheng J X. Analysis of some important newly discovered relics at Erlitou site[C]// Du J D, Xu H. Erlitou site and Erlitou culture: Proceedings of the international symposium on Erlitou site and Erlitou culture, China. Beijing: Science Press, 2006: 18-23. (in Chinese)

|

| [27] |

陈芳妹. 二里头M3——社会艺术史研究的新线索[C]//杜金鹏, 许宏. 二里头遗址与二里头文化研究: 中国·二里头遗址与二里头文化国际学术研讨会论文集. 北京: 科学出版社, 2006: 244-245.

Chen F M. Erlitou M3: A new clue in the study of social art history[C]// Du J, Xu H. Erlitou site and Erlitou culture: Proceedings of the international symposium on Erlitou site and Erlitou culture, China. Beijing: Science Press, 2006: 244-245. (in Chinese)

|

| [28] |

唐际根, 吴健聪, 董韦, 等. 盘龙城杨家湾"金片绿松石兽形器"的原貌重建研究[J]. 江汉考古, 2020(6): 57-66, 141.

Tang J G, Wu J C, Dong W, et al. Reconstructing the animal-shaped artifact adorned with gold foil and turquoise unearthed from Yangjiawan at the Panlongcheng site[J]. Jianghan Archaeology, 2020(6): 57-66, 141. (in Chinese)

|

| [29] |

河南省文物考古研究院, 中国科学技术大学科技史与科技考古系. 舞阳贾湖(二)[M]. 北京: 科学出版社, 2015: 附录(彩版二七).

Henan Provincial Institute of Cultural Heritage and Archaeology, Department for the History of Science and Scientific Archaeology in University of Science and Technology of China. Jiahu, Wuyang, Vol. 2[M]. Beijing: Science Press, 2015: Appendix (color page 27). (in Chinese)

|

| [30] |

朱乃诚. 二里头绿松石龙的源流——兼论石峁遗址皇城台大台基石护墙的年代[J]. 中原文物, 2021(2): 103-110.

Zhu N C. On the origin and development of the turquoise-inlaid dragon of the Erlitou Culture[J]. Cultural Relics of Central China, 2021(2): 103-110. (in Chinese)

|

| [31] |

孙轶琼. 争鸣|"最早中国"究竟在哪里?山西陶寺还是河南二里头?[EB/OL]. [2019-10-24]. https://mp.weixin.qq.com/s/ub0S975Ed-QfyAlOjUDvcA.

Sun Y Q. Controversy | Where is the earliest China? Shanxi taosi or Henan Erlitou?[EB/OL]. [2019-10-24]. https://mp.weixin.qq.com/s/ub0S975Ed-QfyAlOjUDvcA.

|

| [32] |

Aufrère S H. L'univers minéral dans la pensée égyptienne: Essai de synthèse et perspectives[J]. Archéo-Nil, 1997, 7(1): 113-144. Aufrère S H. The mineral universe in Egyptian thought: Synthesis essay and perspectives[J]. Archéo-Nil, 1997, 7(1): 113-144. (in French)

|

| [33] |

Mark S. An analysis of two theories proposing domestic goats, sheep, and other goods were imported into Egypt by sea during the Neolithic period[J]. Journal of Ancient Egyptian Interconnections, 2013, 5(2): 1-8.

|

| [34] |

Moorey P R S. Ancient Mesopotamian materials and industries: The archaeological evidence[M]. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1994: 101-102, 199.

|

| [35] |

Carò F, Schorsch D, Smieska L, et al. Non-invasive XRF analysis of ancient Egyptian and near Eastern turquoise: A pilot study[J]. Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports, 2021(36): 102893.

|

| [36] |

Nicholson P T, Shaw I. Ancient Egyptian materials and technology[M]. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000: 39-40, 177-179.

|

| [37] |

Lythgoe A M. The treasure of Lahun[J]. The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin, 1919, 14(12): 1-28.

|

| [38] |

Wilkinson R H. Symbol & magic in Egyptian art[M]. Thames and Hudson, 1994: 101.

|

| [39] |

Barrois A. The serabit expedition of 1930: Ⅱ. The mines of Sinai[J]. Harvard Theological Review, 1932, 25(2): 101-121. doi: 10.1017/S0017816000001218

|

| [40] |

Copper Developmant Association Inc. Mother nature's masquerade[EB/OL]. [2022-03-20]. https://www.copper.org/publications/newsletters/discover/2005/october/article2.html.

|

| [41] |

The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Pectoral and necklace of Sithathoryunet with the name of Senwosret Ⅱ[EB/OL]. [2022-03-20]. https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/544232.

|

| [42] |

Malek Shahmirzadi S. Tepe Zagheh: A sixth millennium BC village in the Qazvin Plain of the central Iranian Plateau[D]. University of Pennsylvania, 1977: 263-269, 353-354, 382, 459.

|

| [43] |

Herrmann G. Lapis lazuli: The early phases of its trade[J]. Iraq, 1968, 30(1): 21-57. doi: 10.2307/4199836

|

| [44] |

Bache C. Prehistoric burials of Tepe Gawra[J]. Scientific American, 1935, 153(6): 310-313. doi: 10.1038/scientificamerican1235-310

|

| [45] |

Roustaei K, Mashkour M, Tengberg M. Tappeh Sang-e Chakhmaq and the beginning of the Neolithic in north-east Iran[J]. Antiquity, 2015, 89(45): 573-595.

|

| [46] |

Goff B L. The role of amulets in Mesopotamian ritual texts[J]. Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes, 1956, 19(1-2): 1-3. doi: 10.2307/750239

|

| [47] |

Schimmel A. A two-colored brocade: The imagery of Persian poetry[M]. London: The University of North Carolina Press, 1992: 160.

|

| [48] |

Khazeni A. Sky blue stone: The turquoise trade in world history[EB/OL]. [2022-03-20]. http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.1525/j.ctt6wqbh8. California: University of California Press, 2014: 56.

|

| [49] |

The University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology. Ram in the thicket[EB/OL]. [2022-03-20]. https://www.penn.museum/collections/object/242250.

|

| [50] |

The University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology. Lyre fragment bull head[EB/OL]. [2022-03-20]. https://www.penn.museum/collections/object/9347.

|

| [51] |

李延祥, 先怡衡, 陈坤龙, 等. 陕西洛南河口绿松石矿遗址调查报告[J]. 考古与文物, 2016(3): 11-17, 55. https://www.cnki.com.cn/Article/CJFDTOTAL-KGYW201603002.htm

Li Y X, Xian Y H, Chen K L, et al. Report on the investigation of the turquoise mining sites at Hekou in Luonan, Shaanxi[J]. Archaeology and Cultural Relics, 2016(3): 11-17, 55. (in Chinese) https://www.cnki.com.cn/Article/CJFDTOTAL-KGYW201603002.htm

|

| [52] |

先怡衡, 梁云, 樊静怡, 等. 洛南河口遗址出产绿松石产地特征研究[J]. 第四纪研究, 2021, 41(1): 284-291.

Xian Y H, Liang Y, Fan J Y, et al. Study on origin characteristics of turquoise from Hekou mining site in Luonan[J]. Quaternary Sciences, 2021, 41(1): 284-291. (in Chinese)

|

| [53] |

任佳, 叶晓红, 王妍, 等. 二里头遗址绿松石的红外光谱产地识别[J]. 光谱学与光谱分析, 2015, 35(10): 2767-2772. https://www.cnki.com.cn/Article/CJFDTOTAL-GUAN201510024.htm

Ren J, Ye X H, Wang Y, et al. Source constraints on turquoise of the Erlitou site by infrared spectra[J]. Spectroscopy and Spectral Analysis, 2015, 35(10): 2767-2772. (in Chinese) https://www.cnki.com.cn/Article/CJFDTOTAL-GUAN201510024.htm

|

| [54] |

李延祥, 谭宇辰, 贾淇, 等. 新疆哈密两处古绿松石矿遗址初步考察[J]. 考古与文物, 2019(6): 22-27. https://www.cnki.com.cn/Article/CJFDTOTAL-KGYW201906003.htm

Li Y X, Tan Y C, Jia Q, et al. Preliminary investigation of two ancient turquoise mine sites in Hami, Xinjiang[J]. Archaeology and Cultural Relics, 2019(6): 22-27. (in Chinese) https://www.cnki.com.cn/Article/CJFDTOTAL-KGYW201906003.htm

|

| [55] |

李延祥, 于建军, 先怡衡, 等. 新疆若羌黑山岭古代绿松石矿业遗址调查简报[J]. 文物, 2020(8): 1, 4-13. https://www.cnki.com.cn/Article/CJFDTOTAL-WENW202008001.htm

Li Y X, Yu J J, Xian Y H, et al. A survey of the ancient turquoise mining site at Heishanling in Ruoqiang, Xinjiang[J]. Cultural Relics, 2020(8): 1, 4-13, . (in Chinese) https://www.cnki.com.cn/Article/CJFDTOTAL-WENW202008001.htm

|

| [56] |

曹建恩, 孙金松, 孙建军, 等. 内蒙古阿拉善右旗浩贝如古代绿松石矿业遗址调查简报[J]. 考古与文物, 2021(3): 23-32.

Cao J E, Sun J S, Sun J J, et al. Preliminary report on the survey of the ancient turquoise mining site in Alxa League, Inner Mongolia[J]. Archaeology and Cultural Relics, 2021(3): 23-32. (in Chinese)

|

| [57] |

Ahmadirouhani R, Taheri J, Gholamzadeh M, et al. A review on gemstone potentials of Khorasan Razavi Province, Northeast of Iran: A special focus on turquoise gems[J]. Iranian Journal of Geoscience Museum, 2019, 1(1): 57-71.

|

| [58] |

Ghorbani M. The economic geology of Iran: Mineral deposits and natural resources[EB/OL]. [2022-03-20]. Springer Geology, 2013: 66-78. https://rd.springer.com/book/10.1007/978-94-007-5625-0.

|

| [59] |

Kostov R I. Archaeomineralogy of turquoise in Eurasia[C]//Querré G, Cassen S, Vigier E. La Parure en CallaÏs du Néolithique Européen, Oxford: Archaeopress Publishing Ltd., 2019: 387-396.

|

| [60] |

Megahed M M. Archaeo-mineralogical characterization of ancient copper and turquoise mining in south Sinai, Egypt[J]. Archeomatica, 2018, 9(4): 24-33.

|

| [61] |

Resk Ibrahim M, Tallet P. King Den in South-Sinai: The earliest monumental rock inscriptions of the Pharaonic period[J]. Archéo-Nil, 2009(19): 179-183.

|

| [62] |

Beit-Arieh I. New discoveries at Serabit el-Khadim[J]. The Biblical Archaeologist, 1982, 45(1): 13-18.

|

| [63] |

Bloxam E. Miners and mistresses: Middle kingdom mining on the margins[J]. Journal of Social Archaeology, 2006, 6(2): 277-303.

|

| [64] |

Giveon R. Investigations in the Egyptian mining centres in Sinai preliminary report[J]. Tel Aviv, 1974, 1(3): 100-108.

|

| [65] |

Giudice A L, Angelici D, Re A, et al. Protocol for lapis lazuli provenance determination: Evidence for an Afghan origin of the stones used for ancient carved artefacts kept at the Egyptian Museum of Florence (Italy)[J]. Archaeological and Anthropological Sciences, 2017, 9(4): 637-651.

|

| [66] |

Thomalsky J, Stucky R A, Kaelin O, et al. Afghanistan: Ancient mining and metallurgy: Initial project stage[J]. Proceedings of the 9th ICAANE, 2014(3): 647-661.

|

| [67] |

Tosi M, Wardak R. The Fullol hoard: A new find from Bronze-Age Afghanistan[J]. East and West, 1972, 22(1/2): 9-17.

|

| [68] |

Wilkinson T C. Tying the threads of Eurasia: Transregional routes and material flows in Transcaucasia, eastern Anatolia and western central Asia, c. 3000-1500 BC[M]. Sidestone Press, 2014: 105, 130, 136.

|

| [69] |

赖舒琪, 丘志力, 杨炯, 等. 古代青金石的开采和贸易: 基于历史文献及考古发现二重证据的研究进展[J]. 宝石和宝石学杂志(中英文), 2021, 23(4): 1-11.

Lai S Q, Qiu Z L, Yang J, et al. Mining and trading of ancient lapis lazuli: The exploration for a combination of twofold evidence based on historical documents and archaeology discovery[J]. Journal of Gems & Gemmology, 2021, 23(4): 1-11. (in Chinese)

|

| [70] |

Malik N S. Wakhan: A historical and socio-economic profile[J]. Pakistan Horizon, 2011, 64(1): 53-60.

|

| [71] |

龚缨晏. 远古时代的"草原通道"[J]. 浙江社会科学, 1999(5): 59-65. https://www.cnki.com.cn/Article/CJFDTOTAL-ZJSH199905011.htm

Gong Y Y. Ancient "Prairie Passage"[J]. Zhejiang Social Sciences, 1999(5): 59-65. (in Chinese) https://www.cnki.com.cn/Article/CJFDTOTAL-ZJSH199905011.htm

|

| [72] |

杜晓勤. "草原丝绸之路"兴盛的历史过程考述[J]. 西南民族大学学报(人文社科版), 2017, 38(12): 1-7.

Du X Q. The historical process of the prosperity of "Grassland Silk Road"[J]. Journal of Southwest Minzu University(Humanities and Social Science), 2017, 38(12): 1-7. (in Chinese)

|

| [73] |

南京博物院. 徐州土山东汉墓清理简报[J]. 东南文化, 1977(15): 20.

Nanjing Museum. The bulletin of Xuzhou soil Shandong Han tomb[J]. Southeast Culture, 1977(15): 20. (in Chinese)

|

| [74] |

董俊卿, 干福熹, 李青会, 等. 我国古代两种珍稀宝玉石文物分析[J]. 宝石和宝石学杂志(中英文), 2011, 13(3): 46-52. https://www.cnki.com.cn/Article/CJFDTOTAL-BSHB201103013.htm

Dong J Q, Gan F X, Li Q H, et al. An analysis of two ancient precious gems cultural relics[J]. Journal of Gems & Gemmology, 2011, 13(3): 46-52. (in Chinese) https://www.cnki.com.cn/Article/CJFDTOTAL-BSHB201103013.htm

|

| [75] |

中国社会科学院考古研究所. 中国田野考古报告集, 考古学专刊, 丁种第六号, 洛阳烧沟汉墓[M]. 北京: 科学出版社, 1959: 210, 248.

Institute of Archaeology, Chinese Academy of Social Sciences. A collection of reports on field archaeology in China, special journal of archaeology, Ding Species No. 6, Han tombs in Shaogou, Luoyang[M]. Beijing: Science Press, 1959: 210, 248. (in Chinese)

|

| [76] |

李晋栓, 李新铭, 何健武, 等. 河北贊皇东魏李希宗墓[J]. 考古, 1977(6): 372, 382-390. https://www.cnki.com.cn/Article/CJFDTOTAL-KAGU197706003.htm

Li J S, Li X M, He J W, et al. The tomb of Emperor Li Xizong of the Eastern Wei Dynasty in Hebei Province[J]. Archaeology, 1977(6): 382-390, 372. (in Chinese) https://www.cnki.com.cn/Article/CJFDTOTAL-KAGU197706003.htm

|

| [77] |

韩兆民. 宁夏固原北周李贤夫妇墓发掘简报[J]. 文物, 1985(11): 1-20, 97-100. https://www.cnki.com.cn/Article/CJFDTOTAL-WENW198511000.htm

Han Z M. The excavation bulletin of the tomb of Li Xian and his wife in Guyuan, Ningxia[J]. Cultural Relics, 1985(11): 1-20, 97-100. (in Chinese) https://www.cnki.com.cn/Article/CJFDTOTAL-WENW198511000.htm

|

| [78] |

Chen T S N, Chen P S Y. The healing Buddha[J]. Journal of Medical Biography, 2004, 12(4): 239-241.

|

| [79] |

崔欣, 石娜, 朱娜. 文本、礼仪与场域: 清王朝构建藏传佛教王朝化的路径与实践[J]. 青海民族研究, 2021, 32(2): 213-221.

Cui X, Shi N, Zhu N. Text, interpretation and field construction: The route and practice of Qing Dynasty's construction of the royal dynasty of Tibetan Buddhism[J]. Qinghai Journal of Ethnology, 2021, 32(2): 213-221. (in Chinese)

|

| [80] |

Heroldová H. Court beads: Manchu rank symbols in the Náprstek Museum[J]. Annals of the Náprstek Muzeum, 2019, 40(2): 95-106.

|

| [81] |

段渝. 南方丝绸之路: 中-印交通与文化走廊[J]. 思想战线, 2015, 41(6): 91-97. https://www.cnki.com.cn/Article/CJFDTOTAL-SXZX201506016.htm

Duan Y. The Southern Silk Road: China-India transport and cultural corridor[J]. Thinking, 2015, 41(6): 91-97. (in Chinese) https://www.cnki.com.cn/Article/CJFDTOTAL-SXZX201506016.htm

|

| [82] |

Duckworth C N. Imitation, artificiality and creation: The color and perception of the earliest glass in New Kingdom Egypt[J]. Cambridge Archaeological Journal, 2012, 22(3): 309-327.

|

| [83] |

Henderson J. Ancient glass: An interdisciplinary exploration[M]. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2013: 1-4, 14.

|

| [84] |

田昌五. 论衡导读[M]. 北京: 中国国际广播出版社, 2008: 83.

Tian C W. The Annotation of Lun Heng[M]. Beijing: China International Broadcasting Publishing, 2008: 83. (in Chinese)

|

| [85] |

杨伯达. 西周至南北自制玻璃概述[J]. 故宫博物院院刊, 2003(5): 30-35, 94-95.

Yang B D. An overall description of domestic glass from the Western Zhou to the Southern and Northern Dynasties[J]. Palace Museum Journal, 2003(5): 30-35, 94-95. (in Chinese)

|

| [86] |

干福熹, 黄振发, 肖炳荣. 我国古代玻璃的起源问题[J]. 硅酸盐学报, 1978(S1): 99-104, 121-122. https://www.cnki.com.cn/Article/CJFDTOTAL-GXYB1978Z1008.htm

Gan F X, Huang Z F, Xiao B R. The origin problem of ancient glass in China[J]. Journal of the Chinese Ceramic Society, 1978(S1): 99-104, 121-122. (in Chinese) https://www.cnki.com.cn/Article/CJFDTOTAL-GXYB1978Z1008.htm

|

| [87] |

王栋, 温睿, 王龙, 等. 新疆吐鲁番胜金店墓地出土仿绿松石玻璃珠研究[J]. 文物, 2020(8): 80-88. https://www.cnki.com.cn/Article/CJFDTOTAL-WENW202008010.htm

Wang D, Weng R, Wang L, et al. A study of the glass beads imitating turquoise found in the Shengjindian tomb at Turpan in Xinjiang[J]. Cultural Relics, 2020(8): 80-88. (in Chinese) https://www.cnki.com.cn/Article/CJFDTOTAL-WENW202008010.htm

|

| [88] |

湖北省文物考古研究所. 江陵望山沙冢楚墓[M]. 北京: 文物出版社, 1996: 49.

Cultural Relics and Archaeology Institute of Hubei. Jiangling Wangshan Sandmound tomb of Chu[M]. Beijing: Cultural Relics Publishing Company, 1996: 49. (in Chinese)

|

| [89] |

赵永. 中国古代玻璃的仿玉传统[J]. 紫禁城, 2021(6): 32-55.

Zhao Y. The tradition of imitating jade in ancient Chinese glass[J]. Forbidden City, 2021(6): 32-55. (in Chinese)

|

| [90] |

高至喜. 湖南出土战国玻璃璧和剑饰的研究[C]//干福熹. 中国古玻璃研究-1984年北京国际玻璃学术研讨会论文集. 北京: 中国建筑工业出版社, 1986: 53-58.

Gao Z X. Study on glass Bi and sword ornaments unearthed in Hunan[C]//Gan F X. Research on ancient glass in China: Proceedings of 1984 Beijing International Symposium on Glass. Beijing: China Construction Industry Press, 1986: 53-58. (in Chinese)

|

| [91] |

傅举有, 徐克勤. 湖南出土的战国秦汉玻璃璧[J]. 上海文博论丛, 2010(2): 27-38.

Fu J Y, Xu K Q. The glass Bi disk excavated from a Warring States Period tomb[J]. Shanghai Literature and Museum Collection, 2010(2): 27-38. (in Chinese)

|

| [92] |

湖南益阳市博物馆. 战国深绿色谷纹琉璃小环[EB/OL]. [2022-03-20]. http://yiyangmuseum.com/CollectionDetail.aspx?Id=e2763946-3101-4239-9a41-9974773bfa81.

Yiyang Municipal Museum. Dark green glaze ring with grain pattern of Warring States period[EB/OL]. [2022-03-20]. http://yiyangmuseum.com/CollectionDetail.aspx?Id=e2763946-3101-4239-9a41-9974773bfa81. (in Chinese)

|

| [93] |

Leidy D P, Siu W A, Watt J C Y. Chinese decorative arts[J]. The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin, 1997, 55(1): 15-16.

|

| [94] |

中国硅酸盐学会. 中国陶瓷史[M]. 北京: 文物出版社, 1982: 386, 418, 436.

Chinese Ceramic Society. History of Chinese ceramics[M]. Beijing: Cultural Relics Publishing Company, 1982: 386, 418, 436. (in Chinese)

|

| [95] |

汪庆正. 简明陶瓷词典[M]. 上海: 上海辞书出版社, 1989: 252.

Wang Q Z. Concise dictionary of ceramic[M]. Shanghai: Shanghai Lexicographical Publishing House, 1989: 252.

|

| [96] |

(Qing) Pu Jiang, Lu Yun. Huang chao li qi tu shi?: Shi ba juan, Wu ying dian, 1759[EB/OL]. [2022-03-20]. Harvard Library, HOLLIS number: 990080431900203941, seq. 145, Permalink: http://id.lib.harvard.edu/alma/990080431900203941/catalog.

|

| [97] |

The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Foliated dish with floral scrolls[EB/OL]. [2022-03-20]. https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/40766.

|

| [98] |

故宫博物院. 乾隆款松石绿釉凸印夔凤牡丹纹梅瓶[EB/OL]. [2022-03-20]. https://digicol.dpm.org.cn/cultural/detail?id=ff91c777b3c9426db6146d0d60e04fd8&source=1.

The Palace Museum. Turquoise blue porcelain vase embossed with dragon, phoenix, and peony pattern, Qianlong, Qing Dynasty[EB/OL]. [2022-03-20]. https://digicol.dpm.org.cn/cultural/detail?id=ff91c777b3c9426db6146d0d60e04fd8&source=1. (in Chinese)

|

| [99] |

故宫博物院. 祭蓝釉金彩牛纹双系罐[EB/OL]. [2022-03-20]. https://digicol.dpm.org.cn/cultural/detail?id=b10f0626542f4686a41c61dcdef80229&source=1.

The Palace Museum. Lapis lazuli blue double handle porcelain pot with gold color cattle[EB/OL]. [2022-03-20]. https://digicol.dpm.org.cn/cultural/detail?id=b10f0626542f4686a41c61dcdef80229&source=1. (in Chinese)

|

| [100] |

Nicholson P T. "Stone. . . That Flows": Faience and glass as man-made stones in Egypt[J]. Journal of Glass Studies, 2012(54): 11-23.

|

| [101] |

Lansing A. A faience broad collar of the Eighteenth Dynasty[J]. The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin, 1940, 35(3): 65-68.

|

| [102] |

Wilde H. Glass working in ancient Egypt[C]// Klimscha F, Karlsen H J, Hansen S, et al. Vom Künstlichen Stein zum durchsichtigen Massenprodukt (From Artificial Stone to Translucent Mass-Product). Berlin: Universität Berlin und der Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin, 2021: 9-27.

|

| [103] |

Miniaci G. Faience craftsmanship in the Middle Kingdom. A market paradox: Inexpensive materials for prestige goods[C]// Miniaci G, García J C M, Quirke S, et al. The arts of making in ancient Egypt: Voices, images, and objects of material producers 2000-1550 BC. Leiden: Sidestone Press, 2018: 139-158.

|

| [104] |

The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Scarab inscribed for hatshepsut[EB/OL]. [2022-03-20]. https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/549708?searchField=All&sortBy=Relevance&ft=Scarab+++++Hatshepsut&offset=0&rpp=20&pos=3.

|

| [105] |

The British Museum. Pectora: Heart-scarab[EB/OL]. [2022-03-20]. https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/Y_EA7865.

|

| [106] |

Ragai J. Color: Its significance and production in Ancient Egypt[J]. Endeavour, 1986, 10(2): 74-79.

|

| [107] |

Remler P. Egyptian mythology, A to Z[M]. New York: Facts on File, 2006: 47, 67.

|

| [108] |

Hollis S T. Women of ancient Egypt and the sky goddess Nut[J]. Journal of American folklore, 1987, 100(398): 496-503.

|

| [109] |

Bohigian G H. The history of the evil eye and its influence on ophthalmology, medicine and social customs[J]. Documenta ophthalmologica, 1997, 94(1): 91-100.

|

| [110] |

The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Winged goddess[EB/OL]. [2022-03-20]. https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/552609.

|

| [111] |

Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Eye of Horus ring[EB/OL]. [2022-03-20]. https://collections.mfa.org/objects/137306/eye-of-horus-wedjat-ring?ctx=f4870127-b30d-4871-b6db-4dfae920bb0d&idx=1.

|

| [112] |

Shortland A J, Kirk S, Eremin K, et al. The analysis of late Bronze Age glass from nuzi and the question of the origin of glass-making[J]. Archaeometry, 2018, 60(4): 764-783.

|

| [113] |

Kaul F, Varberg J, Gratuze B. Glasvejen[J]. Skalk, 2014(5): 20-30.

|

| [114] |

Archaeology Wiki. Denmark Bronze Age glass beads and Tutankhamun[EB/OL]. [2022-03-20]. https://www.archaeology.wiki/blog/2014/12/10/denmark-bronze-age-glass-beads-tutankhamun/.

|

| [115] |

Horowitz W. Mesopotamian cosmic geography[M]. Winona Lake, Indiana: Eisenbrauns, 1998: 9.

|

| [116] |

Pedersén O. The glazed bricks that ornamented Babylon-A Short Overview[C]//Fügert A, Gries H. Glazed brick decoration in the Ancient Near East: Proceedings of a workshop at the 11th International Congress of the Archaeology of the Ancient Near East (Munich) in April 2018. Oxford: Archaeopress Publishing Ltd., 2020: 96-122.

|

| [117] |

Thavapalan S. Color and affect in Nebuchadnezzar Ⅱ's Babylon[C]// Amrhein A, Fitzgerald C, Knott E. A wonder to be hold: Craftsmanship and the Creation of Babylon's Ishtar Gate. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2019: 127-133.

|

| [118] |

Broberg D. Processional way Babylon Ishtar Gate[EB/OL]. [2022-03-20]. https://www.flickr.com/photos/dbroberg/2384428832.

|

| [119] |

Wikimedia Commons. Entrance of shah mosque of Isfahan[EB/OL]. [2022-03-20]. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Shah_mosque_of_isfahan.jpg.

|

| [120] |

费孝通. 费孝通全集·第14卷(1992—1994)[M]. 呼和浩特: 内蒙古人民出版社, 2009: 211-216.

Fei X T. The complete works of Fei Xiaotong Vol. 14 (1992—1994)[M]. Hohhot: Inner Mongolia People's Publishing, 2009: 211-216. (in Chinese)

|